Why I Write Magical Realism

Guest Blogger: Athol Dickson

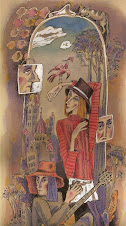

Several novels back I decided to begin including magical realism in my work. I started writing about fires that burn in spite of floods, mysterious cures, angelic interventions, and flying artists. But I’m not a fantasy writer. My novels include magical realism because I want to write more realistically about this world, not because I want to escape it.

Consider this famous quote from The Weight of Glory, by C.S. Lewis:

“It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you can talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare.”

Is Lewis describing the world as it actually is? Or is this merely a creative person’s whimsy, gross hyperbole with only a slight fraction of reality at the core?

I believe the quote is accurate, the way it’s accurate to say the sun is hot or rain is wet. And I’m certain Lewis intended it to be understood that way. So if I write a scene in which one character witnesses another’s transformation into something god-like or demonic, I’m not doing it because I want to create an escapist fantasy. I’m doing it because I want to describe life more accurately.

Fantasy stories need no grounding in the reality of this world. They have holistic logical systems and realities that affect every aspect of their separate universes. They can describe things that never were and never will be on the earth, without direct attachments to the readers’ everyday existence. On the other hand, magical realism by definition remains tethered to the “real” workings of this universe. In fact I believe sometimes just a touch of the magical can make a story more applicable to a reader’s everyday existence than it would be otherwise.

One classic example is in my favorite novel of all time, One Hundred Years of Solitude, where Gabriel Garcia Marquez describes a village stricken by “the insomnia plague.” This mass sleeplessness eventually affects the peoples’ memories. One man realizes he will soon no longer be able to function without help. He puts signs on everything to remind him what they are. Others do it too, and soon the signs are everywhere.

After a while the people realize knowing what to call a thing does not mean one knows what to do with it. They begin to add instructions to the signs. A cow is for milking, and milk is for putting into coffee, and etcetera. At one end of their town, they even erect a sign which says, GOD EXISTS.

Finally into this “quicksand of forgetfulness” comes a gypsy with “a drink of a gentle color.” When that cure takes hold, one healed man’s “eyes became moist from weeping even before he noticed himself in an absurd living room where objects were labeled and before he was ashamed of the solemn nonsense written on the walls . . .”

None of this is technically impossible of course, therefore it is not “fantasy” in the literary sense. It is only highly, extremely, vastly improbable; so completely unlikely to happen that we must at least call it “magical.” Yet Garcia Marquez wrings so much common sense from it, one cannot help but wonder if this “insomnia plague” might be something he has actually witnessed in the world—something not merely magical, but somehow also real.

Perhaps Garcia Marquez (the world’s best known author of “magical realism”) has simply written about life as it really is for the millions who are driven to mass insanity by labor on the treadmill of materialism, exhausted to the point of forgetting why they started running in the first place, yet goaded to keep at it by the omnipresent advertisements which remind them they need this thing and that thing in order to continue to forget who they really are.

I write magical realism because some fires do burn in the midst of floods (think of hope when all seems lost), and all cures are essentially mysterious (no one can explain aspirin), and angels do occasionally intervene (according to the beggars in Mother Theresa’s Calcutta), and there are moments in the midst of work when artists sometimes fly (just ask one if you don’t believe).

In other words, I write magical realism because most of us need to get a little distance from our lives to see them as they really are.

###

"Opposite of Art"

Athol Dickson is a novelist, teacher, and publisher of the DailyCristo website. His novels blend magical realism, suspense, and a strong sense of spirituality. Critics have favorably compared his work to such diverse authors as Octavia Butler (Publisher’s Weekly) and Flannery O’Connor (The New York Times). One of his novels is an Audie Award winner and three have won Christy Awards. His latest story, The Opposite Of Art, is about pride, passion, and murder as a spiritual pursuit. Athol lives with his wife in southern California.

I Left MAGA Host SPEECHLESS on CNN

3 weeks ago